By Christina Lippert

The problem

Christina Lippert

Senior Director of School Support

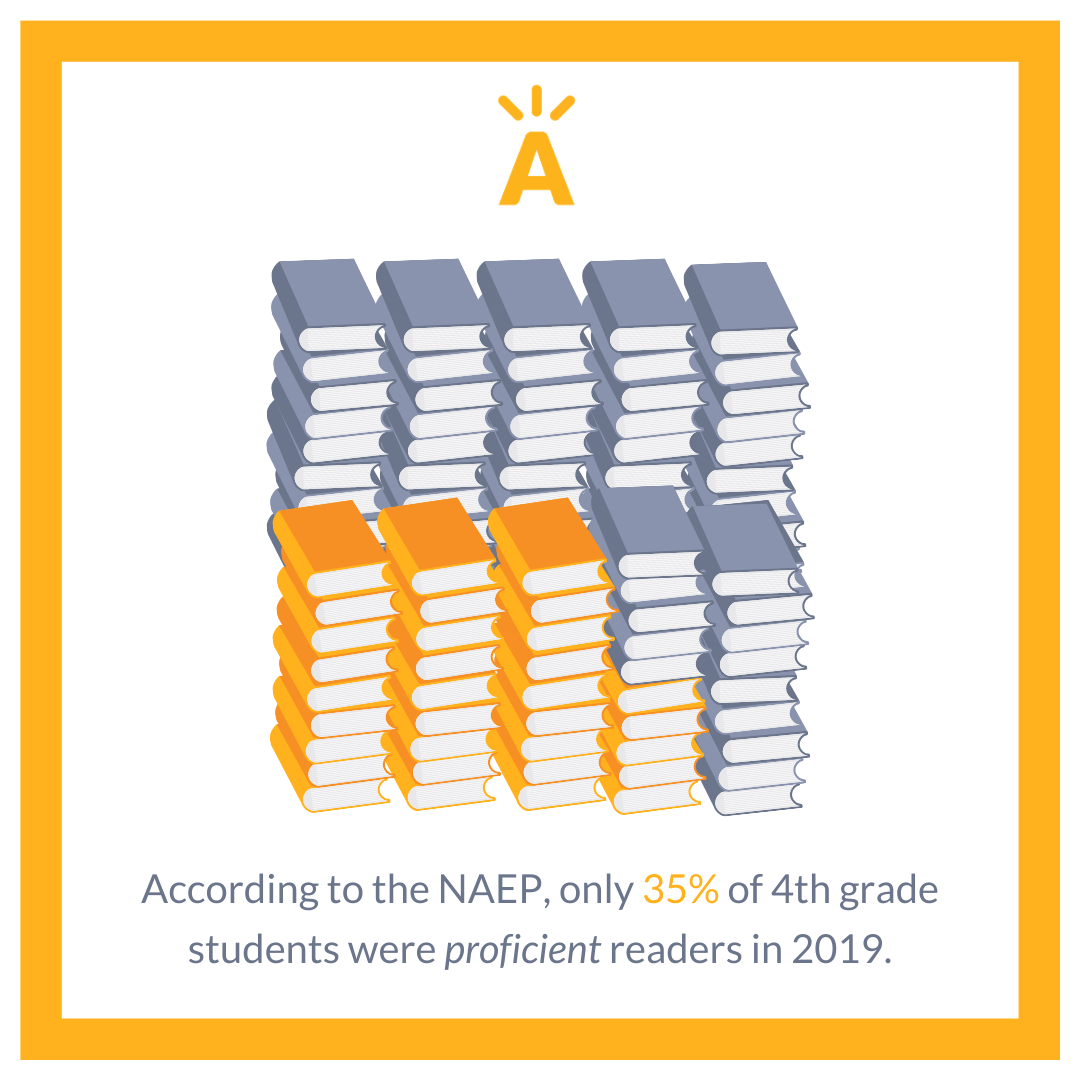

We know that America is faced with a reading crisis. In a pre-pandemic world, only 35 percent of 4th graders were considered proficient readers according to The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) in 2019*.

Further, we see achievement gaps between various student groups and their reading proficiency.

.png)

Now, during this pandemic, data and research continues to sound the alarm bells that students are going to fall academically behind this year and the impact will fall even more disproportionately on our most vulnerable student populations.

Many schools and districts have aimed to solve this crisis by looking to their literacy assessment data for answers. However, in this era of disrupted schooling where instructional time is even more high-stakes and scarce, we must acknowledge that the most common approach to looking at literacy data may be furthering widening student gaps.

The current practice of focusing on reading data that color-codes students as being “on or above grade level” vs. “below-grade level” misses the mark entirely.

In recent years, many schools and districts narrowed their focus to student data that simply tells us if students can read. While knowing at a high-level who can read and/or which students might be at risk for reading struggles is critical data, it’s often not adequate for changing the trajectory of that student’s learning.

The over emphasis on color-coding kids using benchmark assessments is not surprising. It’s efficient, and at first glance, color-coded groupings can appear impressive. Today, most schools and districts are not always sure if students are learning what is being taught, specifically when it comes to foundational reading skills.

The solution

We must focus on opportunities for more granular and targeted data that come when we align our assessments to our instruction. At their best, assessments can and should inform teaching and learning.

.png)

We’ve seen a critical shift in student learning for schools and districts with high-quality curricula that also focus on their curriculum-embedded assessments, especially for foundational reading skills. Many commercially available assessments will tell us that a student is at risk for reading difficulties or even that a student is struggling with the general concept of “letter sounds”. This is not enough! High-level data can lead teachers to reteach much more than needed with a lack of precision, ultimately delaying student progress. This high-level data is equivalent to telling someone the road needs to be repaved, when only a pothole needs to be filled.

When we use curriculum-embedded assessments, we gather and respond to data that tell us specific skills students need to learn based on what has been taught. For example, in a second grade classroom, we’d want to know the specific letter sounds that individual students did not master in last week’s lessons. As a result, the teacher can go beyond providing a blanket intervention focused on “phonics” and, instead, provide differentiated support for students based on sound spelling patterns that still need to be mastered.

| Do this | Not this |

|---|---|

| Re-teaching /oi/ sound as reflected in the “oi” and “oy” sound spelling pattern | Re-teaching “phonics” |

By having granular data on students’ mastery of recently taught concepts, teachers are able to target their interventions. This creates a cycle of responding to data that effectively and efficiently addresses the precise needs of students. In other words, it provides the tools for teachers to fill the “pothole” of isolating particular sound/spelling patterns, rather than wasting time repaving the whole road of phonics. The same holds true for phonological awareness skills.

Our current practice of conducting constant high-level checks on reading skill progression has left us unclear as to the specifics of why a student continues to struggle. Now more than ever, we need to know if students are learning what is being taught-- and schools and districts need to bravely and boldly consider how to do this.

Actions to take toward the solution

.png)

-

Use Curriculum-Embedded Assessments for Foundational Skills: Include curriculum-embedded foundational reading skill assessments (CEAs) from high-quality curricula as a critical component of the literacy assessment strategy

-

Develop Expertise to Use and Respond to CEA Data: Ensure teachers and school leaders receive support and development to both understand how to administer, analyze, and respond to curriculum-embedded assessments focused on foundational skill instruction

-

Align Literacy Assessments to the Science of Reading: Ensure the currently used district/school literacy assessments are not in conflict with the scope and sequence of skills being assessed by the CEAs and/or are in conflict with the science of reading (i.e., combining the F&P Benchmark Assessment System with the high-quality CKLA Skill Strand for foundational skill programming)

It’s time we get specific. We don’t have time to repave roads, but we can find and fill the potholes to support students on their journey to reading proficiency. Our students, particularly those who are most vulnerable, need us to use and take action on the right literacy data.

ANet’s systems-level support and school-based coaching is designed to help you strengthen and align assessment strategy, curricular resources, and instructional pedagogy that aligns to the science of reading comprehension. Fill out our interest form to find out more about how we can support you in filling the potholes.