By Chrissy Allison

My husband and I can’t stand a mess, so we spoon-fed our kids longer than most parents. We even enlisted help from our first child to feed the second. Finally, we had to face the fact that if we ever wanted our son to feed himself, we had to let him hold the spoon.

Many math teachers also hesitate to loosen the reins, to let students get messy and learn by doing. They spoon-feed their classes from the front of the room by demonstrating problems at the board.

It’s no surprise that the 2017 National Assessment of Education Progress showed fourth- and eighth-graders made no meaningful gains in math since implementation of the Common Core in 2015. After all, as we say, the person doing the work is the one doing the learning.

Over the past year, I’ve been collecting examples of schools getting breakthrough results. One thing they all have in common is that they expect students to perform most of the work through productive struggle.

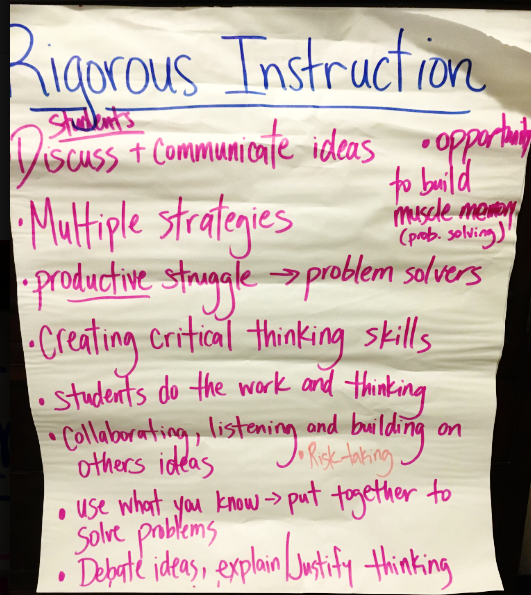

I’ve observed many classrooms where teachers work harder than their students. Yet, when I talk to them about their vision for great math instruction, they describe an environment where students collaborate, solve problems, think critically, and debate ideas as illustrated by the poster below.

.png)

There’s a gap between what teachers aspire for their students and what happens inside many classrooms. How can teachers bridge that gap? Here are five of the most promising practices I’ve learned from educators around the country.

1. Create a vision of what strong, equitable math instruction looks like at your school. Some schools start with the instructional practice guide from Achieve the Core, while others get inspired by instructional videos or TED talks. Teachers and leaders discuss their ideas, come to a consensus, record, and then return to their ideas regularly to gauge progress or to make changes as their vision evolves.

2. Facilitate, don’t “teach.” Teachers should see themselves more as panel moderators, spending the majority of their time asking questions and fostering debate rather than handing out answers. Teaching means sharing knowledge, not dictating it. Replace lectures and note-taking with opportunities for students to solve problems. Walk around the classroom to glimpse the work of students tackling problems independently or to listen to what students are discussing. Foster a lively, curious atmosphere among students.

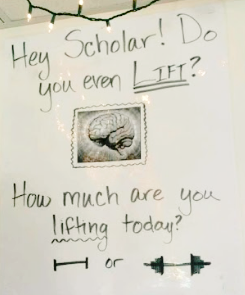

3. Communicate to students the value of perseverance—and what happens when they don’t. Students who are used to being spoon-fed may find it disorienting when teachers expect them to shoulder the lion's share of work. Many teachers find it helpful to teach students that hard work grows their brain. One teacher I know created this poster to keep the lesson top of mind.

Another teacher shows two funny YouTube videos at the beginning of each school year to begin a conversation about what perseverance looks like—and what it does not. One video is of people idly standing on a broken escalator not realizing they can walk up the stairs while the other captures an intrepid baby squirrel climbing a wall. When students encounter a challenging problem, the teacher says, “Remember the squirrels!”

4. Try out a new lesson structure. It’s easy to repeat old patterns of instruction, so it can be helpful to plan lessons using something new like the 5 Practices framework, developed by Margaret Smith and Mary Kay Stein, or 3-Act Math tasks, created by Dan Meyer. Many teachers we work with have found this 5 Practices Planning Guide to be a helpful starting point for carrying out problem-based lessons.

5. Keep it level. Grade-level, that is. Working together to solve problems can be fun, but it’s important to remember that grade-level mathematics should be at the heart of what students are doing. It’s essential for teachers to have a clear goal for each lesson that can help them make decisions about which task to put in front of their students, who they will call on to share solutions, and what questions they will ask to support learning.

Finally, I urge teachers to trust themselves and their students in the process, especially in the beginning. It’s not going to be neat, but remember that a little chaos is good, because the magic is in the mess.

Kids learn to feed themselves by picking up their spoons and getting sloppy. By jumping in and attacking math problems—even if they’re not quite ready, even if the results are messy—your students learn more and will be better prepared for the opportunities awaiting them.

Chrissy is ANet’s former director of math professional learning. Previously, she taught middle school math and was an instructional coach in Chicago.