by Brod Boxley, Ashaki Coleman, and Jasmine Landry

Black students and scholars have long advocated for greater representation of Black history, culture, and achievement in American education.

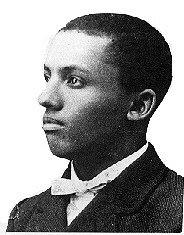

Back in 1926, African-American historian Carter G. Woodson proposed Negro History Week in February (the week of Abraham Lincoln & Frederick Douglass’ birthdays). It quickly spread to schools and public institutions across the country. During the Civil Rights movement of the ’60s, Black college students advocated expanding it to a full month. Since 1976, U.S. presidents have officially designated February as Black History Month.

Why does it matter? As educators, we strive to provide students with both windows and mirrors—windows into the cultures and experiences of others, and mirrors that reflect (and thereby honor and value) their own culture and experiences. Black History Month is an annual reminder of our responsibility to offer these broadening windows and affirming mirrors.

This is a step in the right direction, but it’s a small step. To truly advance equity, Black history and contributions—and those of other underrepresented groups—must be woven into our teaching all year, not just during a single month.

Our students are often our best teachers. In 2016, eleven-year-old Marley Dias launched the #1000blackgirlbooks campaign after being frustrated that she was “only able to read books about white boys and their dogs.” In other words, she needed a better mirror.

As we collectively seek to better understand the role of race, culture, socio-economics and privilege in our schools and communities, let’s re-commit to actively reflecting on our own and others’ experiences, perspectives, and identities. Let’s make space for both windows and mirrors to enhance instruction and positively impact students’ lives.