Many districts are investing heavily in curriculum to improve teaching and learning. But you’ll only get so far if you only pay attention to curriculum, because assessments can actively work against a good curriculum. ANet helped LDOE grapple with this dilemma.

When the Louisiana Department of Education adopted a new, high-quality curriculum, they expected it to have a rapid positive impact on student learning.

But Rebecca Kockler, the department’s assistant superintendent of academics at the time, knew something was off after she and her team of administrators repeatedly observed teachers re-teaching skills, causing classes to break out of sequence with the curriculum.

In one English class, she saw one teacher drilling students on the concept of main idea over and over again while they read The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe. Curious, she took teachers aside.

Teachers complained about the complicated web of assessments. “They were getting all these confusing messages about what they were supposed to teach,” Kockler says.

“The test tells them one set of values about what they should teach and the curriculum tells them another,” Kockler says. “Often teachers will abandon the curriculum messages for the assessment messages, because the assessments come with some other implication like grades and evaluation.”

“The test tells them one set of values about what they should teach and the curriculum tells them another. ”

LDOE, like many districts across the country, was focused on curriculum as the key lever for improving student learning; but misalignments in assessments were undermining their effort. They turned to ANet’s System Advising team for help.

“Assessments are powerful because they drive the actions of teachers and influence their behavior,” explains ANet’s Molly Depasquale. “But if they’re not aligned with the curriculum, teachers receive conflicting signals about what they should prioritize in their classrooms. LDOE had to overhaul its assessment strategy to take advantage of its investment in curriculum.”

The predicament the LDOE faced is widespread, says Alexandra Clarke, senior vice president and general manager for ELA curriculum at Amplify, a curriculum and assessment company. Assessments and curriculum are regarded separately instead of two parts of a whole.

“Often districts have an existing curriculum and then want to overhaul the assessment system but haven’t really thought about how they fit together,” she says. “There are a lot of open questions about the way the two relate and how teachers can use information from assessments to modify instruction. It's hard to get both right at once.”

22 lost days

The confusion, Molly’s team discovered, arose from a mishmash of unaligned assessments. Different offices at state, district, and school levels required different assessments for different purposes. Some assessments fulfilled directives that no longer existed.

Teachers throughout Louisiana were inundated with data from assessments—but lost as to how to best tailor instruction in their classrooms. Weekly quizzes, required for grading purposes, yielded data used in PD sessions, but benchmark assessments gave them completely different data. Both, however, had no relevance to the data teachers collected on how well students performed in class.

“There were some mandates at some point in time that may have ended, but nobody knew,” Kockler says. “They layered on another assessment for grading purposes, and then they layered on another assessment for evaluation, and then they layered on another assessment for a special education requirement.”

“I almost fell out of my chair. I didn’t think we were taking as much time from kids’ day-to-day learning as we actually were. ”

Digging into those myriad layers unearthed a troubling discovery.

“We found on average, for a seventh-grader, our districts were giving up something like 22 days of instruction just for assessment purposes, which was ludicrous,” Kockler says. “All these different people didn’t know they were asking teachers to do all these assessments in their schools.”

The finding shocked Kockler.

“I almost fell out of my chair. I didn’t think it was as bad as it really was. I didn’t think we were taking as much time from kids’ day-to-day learning as we actually were.”

The experience underscores how important it is for districts to have the right assessment strategy in place to support the curriculum, Kockler says.

Learn more about the benefits of honing your assessment strategy.

“A good assessment strategy influences a teacher’s understanding of what kids are and are not learning. It influences the decisions they make day to day about how to adjust what they spend their time doing. When those decisions are based on bad data because they’re from bad assessments, kids end up getting low-quality instruction.”

A holistic view, a genuine partnership

As ANet and LDOE audited the assessments in use, they asked teams across the organization about purpose. The lack of clarity stunned Kockler.

“The number of times nobody could identify who used the data from the assessments was troubling,” she says. “They were doing it because of years of practices we told them to do. They felt they were doing the right thing.”

The ANet team turned its attention to building support for a set of common values regarding assessments. Kockler admits she was skeptical. She didn’t relish the idea of sitting around discussing touchy-feely things like values; she felt impatient to fix the department’s problems. But, she soon realized, “I was totally wrong.”

“That approach was really powerful. Our districts loved ANet because the coaching was without judgment. They felt it was a partnership. The reason why that matters is because there were a lot of mindsets that had to change across different teams, like the K-2 director who can’t give up this random reading assessment that nobody uses.”

STUDENTS

IMPACTED

The work had an enormous impact. LDOE agreed on what assessments to keep or discard and what they wanted to measure. ANet, Kockler says, “kept the team grounded on something beyond turf wars on who gets to decide how assessments are used in the district.”

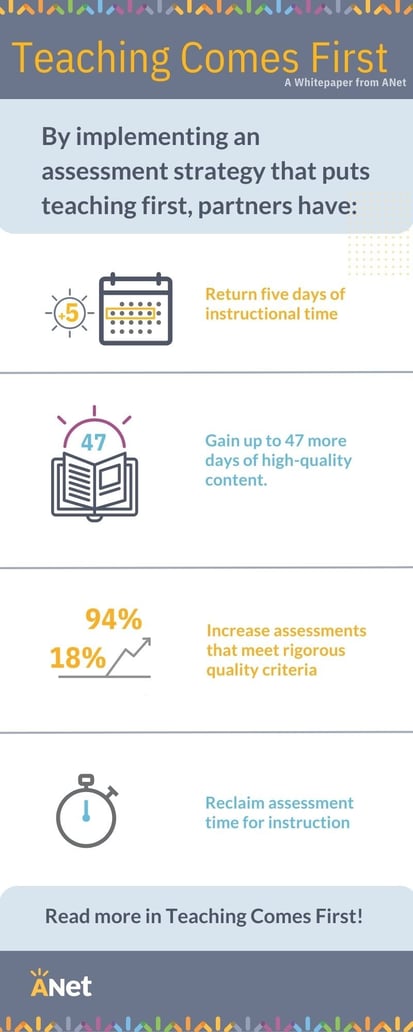

At the end of ANet’s engagements with districts, 94% more assessment content, on average, came from Tier 1 (high quality) sources; 100% of formatives and interims were intended to serve instructional purposes; and teachers got an entire week of instructional time back over the course of a year.

With a clear, streamlined new assessment strategy, teachers are getting the information they need to teach the new curriculum effectively—to the benefit of 50,000 students’ learning.